Background

The performance of the Italian army is still considered by many as a case of a badly led force that preferred to run away when faced with battle, couldn’t wait to get home to have spaghetti and that had to be rescued by Rommel personally and/or the Germans more generally every time it went into battle.

This caricature view, which sees the Regio Esercito’s performance almost entirely through the lens of the COMPASS operation and the Rommel Papers still has many followers and in the English-speaking world you cannot go much wrong by heaping scorn on the Italian armed forces.

Naturally, this has led to a counter-movement, which claims the exact opposite, i.e. that the Italian armed forces were the rock stars of World War 2, consistently rescued the day, and performed outstandingly throughout.

Regular readers will not be surprised to hear me say that I consider the truth can be found somewhere between these two extremes.

The Italian Army at War

There can absolutely no doubt that the Italian soldiers could and did fight, and in many instances they did so very well indeed. In particular the Ariete and Trieste Divisions and the light infantry Bersaglieri units stand out in terms of their performance. Also, like in most armies, Italian gunners were of the die hard variety and there are many instances where they are reported to have died over their guns rather than retreat. Leadership, esprit de corps, training, supply and equipment made the difference. Just like in any other army.

Regular infantry divisions were more challenged in this regard, and I consider that the situation is maybe similar to the late war German army where you can see some divisions that were performing very well until the last days of the war, while others were essentially just speed bumps in any major advance by an enemy force.

Ariete Armoured Division M14/41 medium tank of 132^ Reggimento Carri advancing in western Cyrenaica in January 1942. Note the add-on armor and stowed items and fuel, indicating a veteran crew on their way to work. Colourised by “Painting the Past”.

Structural Issues

There were severe structural issues in the Italian army, affecting its ability to perform in combat. While the different rations for officers and men are often cited, the actual problems were much more serious. For example, each regular infantry division only had two infantry regiments, with only two rifle battalions each. Prior to January 1942, regimental support weapons were concentrated in an ‘accompanying arms’ battalion in each regiment. These had a good number of anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns, but only 81mm mortars, while at infantry battalion level the heaviest support weapon was a 45mm mortar, alongside some not particularly good heavy machine guns and obsolete anti-tank guns. The division also had a division-level mixed arms escort battalion with 81mm mortars, AA, and AT guns, which could be used to reinforce either of the regiments and could provide some anti-air cover to the division. Nevertheless, the divisional structure was top-heavy, with rifle battalions being weakened in favor of centralized assets. By comparison, German infantry battalions had organic heavy machine guns of superb quality and 81mm mortars, while infantry regiments had a full company of AT guns and an infantry gun company with 75mm and 150mm guns, as well as a pioneer company.

The Italian divisions also lacked a powerful artillery component, with the main divisional gun being an outdated 75mm gun, and the heavy artillery element provided by 100mm guns, with 12 guns of each type for a total of 48 guns plus a mixed AT/AA gun battalion. This number was very low compared to the 72 guns in an Empire infantry division, and also compared badly in terms of weight of fire to the German divisions, which had 36 105mm howitzers in two battalions and a heavy battalion of 12 155mm howitzers. Heavier artillery in the Italian army was allocated at Corps level, leading to better concentration but less flexible response.

Anti-tank defense was provided either by German 37mm AT guns, which by 1941 were completely obsolete, or the somewhat better Italian 47/32 gun, which was however still challenged in terms of performance.

This overall firepower differential, both in terms of absolute weight of fire and where it was controlled no doubt made a difference on the battlefield.

The manpower strength of an Italian infantry division was also very low, between 1/3rd to half of that of a German or British infantry or armoured division. This meant that the division could not absorb prolonged combat losses without becoming ineffective, and e.g. had no means to rotate rifle battalions in and out of the line easily. Overall this made the Italian infantry an inflexible tool, with many command decisions moving up to Corps level, which would in other armies be handled at divisional level.

Finally, at the start of CRUSADER, many Italian infantry divisions were missing crucial elements of their combat forces, which were stuck in Italy or had been lost on the way to North Africa due to the interdiction campaign waged by the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force against the North Africa transports. This further weakened them.

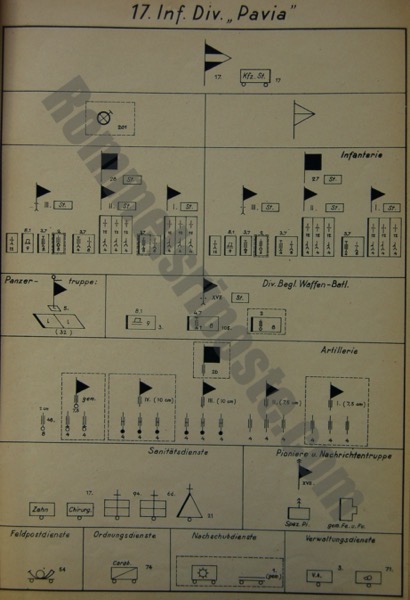

OOB and ToE of 17 Pavia Infantry Division, XXI Corps, ca. autumn 1941. Rommelsriposte.com Collection

The document above provides a clear example of the structural and specific shortcomings in the organisation of the Italian infantry divisions. First off, units in a dotted box are not present, having been sunk on the way or stuck in Italy. More than half of the artillery as well the regimental staff was thus missing, together with supply services, the 20mm AA gun company of the divisional escort battalion and the two regimental support battalion, some of the AT gun companies and divisional signals. The division had been reinforced by two companies of light tanks, really tankettes, which did not have any combat value. AT defense was provided by the obsolete 37mm gun.

The German View

The German view of the Italian performance is quite mixed as well, including that of Rommel himself. While he sometimes did admire and defend Italian troops and commanders against unwarranted criticism, as in the case of the GOC 55 Savona Infantry Division, General Fedele de Giorgis, he also was critical of the Italian performance overall, and did not hesitate to blame the Italians for failed operations, or accuse them of not being up to requirements as a justification for his request for additional German troops.

In this regard, it is however important to note that put into similar situations, as e.g. Division z.b.V. was during the Tobruk breakout on 21 November 1941, the German troops did not perform appreciably better, and seem to have gone into captivity at the same rate as their Italian comrades.

Nevertheless, ultimately Rommel relied heavily on Italian units, and in particular in the early stages of his operations in North Africa, they feature highly.

The Evidence – The Siege of Bardia and Halfaya

When Bardia and Halfaya were cut off at the end of the battles around Tobruk in early December 1941, the German commander of Sector West, General Schmitt, wrote highly critical and disparaging letters about his fellow commander Fedele de Giorgis, accusing him of just looking for an excuse to surrender. Ironically, in the end de Giorgis held his position until he ran out of water, which was for more than two weeks after General Schmitt had surrendered at Bardia. He did not have to do so, having received permission to surrender before. de Giorgis holding on to Halfaya was a critical element in denying the Empire forces a secure supply line along the Via Balbia, and thus contributed to the supply problems in the forward area which allowed Rommel’s counter offensive to be successful at the end of January 1942.

Both Schmitt and de Giorgis received the Ritterkreuz for their action, but one has to wonder how much Schmitt deserved his. de Giorgis is one of the few Italians to have received it.

General Fedele de Giorgis after the war as Commander of the Corpo dei Carabinieri. Museum of the Carabinieri.

The Evidence – Bir el Gobi, 19 November 1941

The arrogance of the Empire commanders towards the Italians is probably shown nowhere better than in the case of 22 Armoured Brigade attacking the Ariete division’s position at Bir el Gobi on 19 November 1941, during the initial advance of 30 Corps. In some books the excuse is trotted out that neither the GOC of 7 Armoured, General Gott, nor the CO of 22 Armoured Brigade, Brigadier Scott-Cockburn, were aware that Ariete was actually at Bir el Gubi. While that may or may not be true, there was no excuse for that ignorance. The division had clearly been placed in this locationby Empire intelligence services, four days before the attack. If Gott and Scott-Cockburn didn’t know they hadn’t paid attention to their intel briefings. If they did, it is apparent that they arrogantly assumed they could swipe away the Italians.

Eighth Army Intel Document placing Ariete at Bir el Gobi, 15 November 1941. Note the low manpower strength of Ariete. Rommelsriposte.com Collection

What happened next was that General Gott launched Scott-Cockburn’s brigade at the Italian position, for reasons unknown, but probably expecting the Italians to foldwhen faced with 160 British tanks, as they had done so often during COMPASS. This did not happen, and after a few hours of combat the three inexperienced tank regiments of 22 Armoured Brigade which, to add insult to injury, had been badly led in what was their first action of the war, withdrew to their starting position with heavy losses, concentrated in 2 Royal Gloucestershire Hussars.

At the end of 19 November therefore, 22 Armoured Brigade had lost anywhere between 25 and 50 tanks, and had very little to show for it. The location would be revisited about two weeks later, this time with 11 Indian Brigade supported by 8 R.T.R. attacking the Giovani Fascisti (Young Fascist) infantry that had dug in there. This again ended in failure for the Empire forces, with heavy losses.

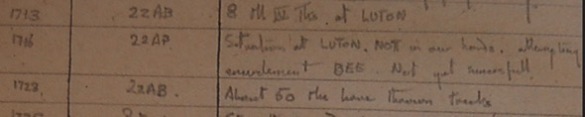

7 Armoured Division Message Log, 19 November 1941. Rommelsriposte.com Collection

LUTON is the code name for Bir el Gobi. The message that 50 tanks did ‘throw tracks’ could be read as code (radio messages were sent in clear) for these tanks having been disabled during the battle. Of particular note is the claim that eight German Mk. IV tanks backed up Ariete. This is of course utterly false, and the Italian troops had no support from the Germans.

The conclusion from the fight at Bir el Gobi on 19 November is that General Balotta, GOC Ariete division, had clearly outthought and outfought General Gott and Brigadier Scott-Cockburn, sitting them down for an applied lesson in combined arms warfare that both of them failed to digest however. Balotta was a veteran of World War One, a gunner by training, and a very successful officer. After serving in North Africa he took command of the corps artillery of the Italian army in the Soviet Union. He survived the war.

There were two major tank battles on 19 November. 22 Armoured Brigade against Ariete, and the reinforced Panzerregiment 5 as Kampfgruppe Stephan against 4 Armoured Brigade. A fair assessment would be that the only ones coming out of these two engagements with any credit at operational level were the Italians. Stephan failed to push and did not achieve his objective. 22 Armoured Brigade, see above. 4 Armoured Brigade failed to concentrate and were rescued by the performance of 8 King’s Royal Irish Hussars, which was the regiment that stood between the brigade and annihilation that afternoon. By contrast, Balotta had not only held his position, but inflicted serious losses on 22 Armoured Brigade in doing so, and driven them off the el Gobi position for good.

The victor of Bir el Gobi, General Mario Balotta, GOC Ariete Division in North Africa, probably 1941 with an M13/40 medium tank. Wikipedia.

Mass Surrenders

A major reason for the low combat value ascribed to the Italian army are repeat incidents where hundreds of soldiers were collected into captivity without much or indeed without any resistance. Beda Fomm looms large in this, and this reputation isn’t overcome by incidents where the Italian forces fight to the last and force the attacker into putting in some considerable effort to overcome them.

It is nevertheless important to note that mass surrenders of operationally outfought forces weren’t an Italian monopoly. As events at Mechili in April 1941, Coefia east of Benghazi in January 1942, the Knightsbridge Box, Fuka Pass and of course in Tobruk in June 1942 and Mersa Matruh in July 1942 showed, Empire forces were perfectly capable of this as well. We could also mention Crete, Greece, Dunkirk, or Singapore. Yet nobody is drawing the conclusion from these mass surrenders that the Empire forces as a whole were shy and just interested in going home to their warm ale.

The Tobruk Fortifications

Another example of the Italians being written out of history relates to the 6 Australian Division’s stand at Tobruk in April/May 1941. Reading the war diaries and combat reports on both sides, it is clear that the defense stood and fell with the performance of the fortification system, which the Axis troops found an impossible nut to crack. These fortifications were all built by the Italian army to defend Tobruk, a fact that is often overlooked.

Empire War Diaries

As already noted above, assessing the task of Italian army performance isn’t made any easier or better by Empire histories in some cases engaging in what appears to be outright lies or at least deliberate misrepresentations, to continue to reinforce the narrative of the bumbling Italians who just weren’t very good. The example from Bir el Gobi above is of course one instance, but there are other reports, where resistance by small Italian garrisons against heavy odds is simply ignored or belittled. A good rule of thumb (as always) is to try and find evidence from the Italian side for any instances where their performance is written off.

An example to the contrary is the New Zealand Official History, where at least in some instances such as The Relief of Tobruk credit is given where due regarding a night attack of 24 and 26 Battalion on a German/Italian position held by Trieste division’s Bersaglieri battalion.

From the plumed hats of those lying dead they were identified as Bersaglieri, and closer examination showed them to be of the 9th Regiment. Many of those who went through this night and saw these dead foes in the morning had occasion sharply to revise their opinion of Italians as fighting men.

Bersaglieri Monument, Porta Pia, Rome. Wikipedia.

Outside North Africa

Italian forces also fought in other theatres, such as Russia and East Africa. Again it was a mixed performance, but it is worth noting the quite legendary fighting retreat of the Alpini (Mountain) Corps of Italian 8th Army in Russia. In East Africa, Italian forces held the mountain position of Gondar for over half a year after the surrender of the Duke of Aosta with the main body of forces at Amba Alagi.

Conclusion

The aim of this article is not to claim the Italian army was an unbeatable super army. It is merely trying to set out that assessing its performance is a differentiated story that requires the analysis of a lot of primary and secondary documents and an overall fairer consideration than is usually given.

Serious historians of the Desert War know and understand this, but it is a myth that needs engaging continuously due to 80 years of history telling us something else.

Further Reading

- Operations of XXI. Corps in North Africa

- Italian Division Strength at the end of the Battle

- Bardia, Halfaya, and the Counter-Offensive

- Ariete at Sidi Rezegh Pt. I

- Ariete at Sidi Rezegh Pt. II

- Bir el Gobi 19 Nov 1941

- Bir el Gobi 5 Dec 1941

- XXXI. Guastatori (Assault Engineer) Battalion

- 1st Carabinieri Paracadutisti Battalion

- 55th Savona Infantry Division

- Tobruk Fortifications

The Italians won the 1st gun armed tank battle in North Africa when Col. Aresca and the 4th Medium Tank Brigade with M11/39’s drove off the 7th Armored Brigade with A9 Cruisers at the Battle of Gabr al Ahmar, early August 1940. No English language coverage of the battle in any detail. Proves your point! During Operation Compass, The Matilda was a shock to the Italian 10th Army (as it was to the Germans in France) and a game changer.

LikeLike

Thanks for the example Gary!

LikeLike

Back in the 1980s I served in the Territorial Army (the part time reserve of the British Army), the Battery Sergeant Major of the Artillery unit had served in WW2, in North Africa and always would say the Italian Artillery was ‘Bloody good’.

LikeLike

The Italians fought a brave rear guard action at the second battle of Alamein using 75mm self propelled semovente guns. These guns were the first 75mm tank guns in Africa. There were no British equivalent on a tank until 1944. Fortunately there was never enough to make a difference especially when the Americans started supplying grant and shermans

LikeLike

Hi Wynne

The Italian 75mm were shorter-range howitzers, similar to the German 75L24 on the Panzer IV. They weren’t high-performance AT guns, but with hollow-charge munitions could be dangerous, if they managed to hit their target (a problem beyond 500m). The Semovente’s were a good design, low-slung and very flexible, which would have helped.

The 75mm gun on the Grant tank was superior to the gun of both the Semovente da 75 and the Panzer IV with the short-barreled gun.

All the best

Andreas

LikeLike