Background

The failure of Eighth Army to defeat Rommel’s Afrika-Korps in the opening days of the operation, and instead seeing its tank force melt away in the battles at Bir el Gobi and Sidi Rezegh, led to high levels of anxiety amongst the command of Eighth Army, and disagreement between General Cunningham, commanding the army, General Norrie, commanding the now much depleted 30 Corps, the armoured strike force, and General Galloway, the Chief of Staff of the army. On 22 November therefore, Gen. Cunningham asked Auchinleck to come to Eighth Army HQ – itself an indication that he was no longer sure in his decision-making.

Then, following the heavy defeat at Sidi Rezegh on 23 November and the loss of almost all cruisers and 5th South African Brigade, early on 24 November, German tanks were speeding on their way east as the spearhead of Rommel’s determined counter-stroke, known as the ‘Dash to the Wire’. It caused a complete breakdown in command and a desperate race to the east by echelon troops trying to get out before they were put ‘into the bag’. General Cunningham himself barely escaped with his plane taking off after a visit to 30 Corps HQ while being shelled by German tanks approaching the landing strip where he boarded it. During the flight to visit General Godwin-Austen at his HQ at Sidi Azeiz, Cunningham observed the German tanks himself.

Command Decisions

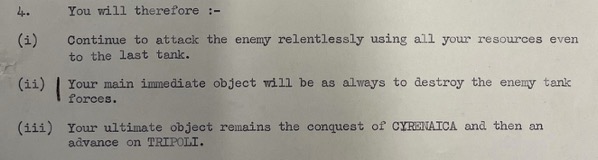

In light of the situation, and of the concern raised by Godwin-Austen during this meeting, who after an initial burst of confidence at 0900 hours on 24 November amended his letter to Cunningham at 1245 hours suggesting to tread with caution, Cunningham met Auchinleck at his HQ. The initial reaction to the situation by General Auchinleck, who was quickly appraised, was that everyone was to hold their nerve and that the attack would have to continue, and orders were issued accordingly.

Auchinleck’s Order, issued 24 November 1941. NAM.

Yet, the next day Auchinleck had thought the matter over, discussed with Air Marshal Tedder and Minister of State Lyttleton, and Gen. Cunningham was sacked and replaced by Gen. Ritchie, Auchinleck’s Deputy Chief of Staff. The reason for this was clearly given as that Auchinleck had lost confidence in Cunningham’s ability to continue to conduct the operation in the offensive spirit he desired. The official despatch by Auchinleck, as well as Molony ’s Official History written in the 1950s, refer to this in a factual way, although the despatch talks about Cunningham’s anxiety about the situation as a reason.

Auchinleck’s letter removing Cunningham from command of Eighth Army. NAM

Accompanying the official letter was a hand-written letter by Auchinleck, in which he elaborated on his thinking. Most crucially, this letter requested Cunningham to agree to be placed on the sick list, for the purpose of what we would today call operational security. Auchinleck’s cable to the C.I.G.S. on 25 November, informing Field Marshal Dill of the decision, also makes this clear. It is in The Auchinleck Papers:

Cipher message, Auchinleck to Field Marshal Sir John Dill, CIGS, 27 November 1941

Cunningham took blow very well and consented to go to hospital ALEXANDRIA where he is now incognito (.) He is NOT repeat NOT really ill but his eyes have troubled him and he admits being tired (.) Because of eye trouble he recently suddenly gave up smoking which may have had something to do with it (.) He can NOT repeat NOT remain indefinitely in hospital incognito and I shall be grateful if you will order him home (.) Am asking him how he would like to travel (.) I hope he may be fit for further employment later.

JRL, AUC 476

The further contemporary exchange of letters, all written by the end end of November 1941 and sent between the two men, leaves no doubt that the hospitalization of Gen. Cunningham served primarily the purpose of covering up the real reasons for his removal.

Excerpt from Auchinleck’s personal letter accompanying the official letter on 25 November 1941. A transcription of Auchinleck’s letter by Cunningham. NAM.

Letter – Auchinleck to Cunningham, 27 November 1941. A transcription of Auchinleck’s letter by Cunningham. NAM.

Letter – Auchinleck to Cunningham, 27 November 1941. A transcription of Auchinleck’s letter by Cunningham. NAM.

In the end, following an initial examination by a duty doctor, Cunningham was examined by Col. Small, the highest-ranking medical officer in theatre. The result of this examination is given in The Auchinleck Papers:

Medical report on Lieutenant General

Sir Alan Cunningham by Colonel W. D. D. Small, Consultant Physician, 30 November 1941

I examined General Cunningham on 29th November at No.64 General Hospital, and ascertained all medical facts relevant to his case.

I was informed that when he was admitted to hospital, on the evening of November 26th, he was exceedingly tired and showed signs of strain. His long and heavy responsibilities had culminated in a period of about a week with practically no sleep. His voice was weakened. When speaking he tended to break off in the middle of sentences. He showed a marked tremor of the hands.

It appears that about a month ago he consulted an ophthalmologist who found a scotoma affecting the right eye. He was advised to stop smoking, and did so. It is to be noted that sudden cessation of tobacco in a heavy smoker often produces marked irritability and unrest.

Since admission to hospital he has slept soundly each night. At the time of my examination, he looked rested, and all signs of strain had disappeared except a slight general increase of his deep reflexes. His general physical state is good. His voice is normal. The tremor has disappeared. He is composed, and very alert and mentally active. There is no evidence of any “nervous breakdown”.

On admission to hospital, General Cunningham was suffering from severe physical exhaustion. Fortunately he is making a rapid recovery. I consider that he requires a further period of rest, of at least a month, before he returns to duty.

JRL, AUC 497

The politicization of Cunningham’s ‘sickness’

There is little evidence from the time when he was removed from command that Cunningham was really sick. Auchinleck’s letters are clear in this regard, that there was no medical reason for the sacking. But two letters from Gen. Arthur Smith, Auchinleck’s Chief of Staff, indicate a different perspective.

Private letter from Gen. Arthur Smith to Gen. Cunningham, 12 July 1942. NAM.

Official letter to Cunningham on 1 Dec 1941 from Gen. Smith. NAM.

The matter of Cunningham’s sickness was then introduced into the public by Churchill himself in his update on the war situation on 9 December 1941:

The first main crisis of the battle was reached between 24th and 26th November. On the 24th General Auchinleck proceeded to the battle headquarters, and on the 26th he decided to relieve General Cunningham and to appoint Major-General Ritchie, a comparatively junior officer, to the command of the 8th Army in his stead. This action was immediately endorsed by the Minister of State and by myself. General Cunningham has rendered brilliant service in Abyssinia and is also responsible for the planning and organisation of the present offensive in Libya, which began, as I have explained, with surprise and with success and which has now definitely turned the corner. He has since been reported by the medical authorities to be suffering from serious overstrain and has been granted sick leave.

Considering the quoted report by Col. Small above, the statement by Churchill is clearly playing fast and loose with the facts – strain becomes ’serious’, and a request to play along by allowing himself to be admitted to hospital becomes ‘granted sick leave’ as if he had requested it for himself, even though Small found him perfectly fine.

At the same time, the system worked to protect itself. On 22 December, Cunningham was put before a medical board, which classed him ‘D’, temporarily not fit for service, and put him on medical leave. At this point, almost one month after the events, the medical justification for his sacking was thus created.

This statement elicited a strong challenge by an MP on 8 January 1942, in which Cunningham’s sickness was seriously questioned, implying he had been sacked for being a realist:

The Prime Minister, when speaking on 11th December, backed the military spokesman in Cairo as having made a reasonable anticipation of what was going to happen and said that, on the whole, he thought he was right. But does not the House recollect that within the last few days there has been a report in the newspapers to the effect that General Cunningham, just before the attack started, said that the fight would be hazardous and that, while it might end quickly, it would be a very risky proceeding having regard to the forces which he knew would be against him. It is an astonishing thing that, after having given that warning, General Cunningham is apparently now at home ostensibly because he is sick, though I did not seem to notice any particular frailty about him when I saw him walking about the other day. (Mr. Stokes, 8 Jan 1942 here)

In a future update, Churchill then doubled down on Cunningham’s performance, in his war update on 27 January 1942:

Here was a battle which turned out very differently from what was foreseen. All was dispersed and confused. Much depended on the individual soldier and the junior officer. Much, but not all; because this battle would have been lost on 24th November if General Auchinleck had not intervened himself, changed the command and ordered the ruthless pressure of the attack to be maintained without regard to risks or consequences. But for this robust decision we should now be back on the old line from which we had started, or perhaps further back. Tobruk would possibly have fallen, and Rommel might be marching towards the Nile.

Suddenly, going from being responsible for excellent planning and organization of the Libyan campaign, Cunningham would have lost it, and Egypt into the bargain. This was beginning to look like character assassination.

This was strong stuff, but not everyone bought it. It lead to what looks like an immediate challenge by Mr. Stokes here. Later, it was understood that there was a serious question about the veracity of the nervous breakdown or sickness. More importantly, at least one MP understood that Cunningham had been thrown under the bus by Churchill:

[…]is it not a fact that General Cunningham has never been ill and that all this unfortunate affair has been used to cover up the over-statements made in this country by the Minister of Defence about the Libyan Campaign? (Stokes, 3 Mar 1942 here)

Another MP took up the case a week later, requesting information on Cunningham’s future employment (see here).

The invention of this sickness, and the ruthless pursuit of corroborating this invention, in the face of the available evidence to the contrary is the consequence of the initial ruse that was used by Auchinleck, on his own responsibility, to bury the news of a disagreement at the highest command levels in the Middle East. The ruthless exploitation of this ruse by Churchill was not something Auchinleck planned for I guess, but he could have foreseen it, as Churchill’s character was hardly a secret.

Conclusion

In the end, it is apparent that while not suffering from a nervous breakdown, Cunningham was tired and under high levels of stress. It is clear that he could no longer convince Auchinleck (or indeed his immediate leadership team at army HQ) that he was the man for the job. Auchinleck then concluded that a more pliable tool was needed, and found it in the form of General Ritchie. In fact, as Auchinleck told Churchill a few days later, probably in response to Churchill’s request to take over command of the army directly, he had considered just this course of action, but dismissed it. Ritchie it was, but with Auchinleck just hovering behind him.

Nevertheless, given the heavy responsibility of fighting the largest British offensive against the Germans in World War 2 to date, it is also clear to me that Auchinleck needed someone he could trust to fight the battle in the highly aggressive way he wanted it to be fought. The idea, as set out by Dennis Vincent in his recent PhD on Cunningham’s leadership, that given a few days rest Cunningham could have recovered from the strain he was under, does in my opinion not fly. There was no time for him to recover. On 24 November the battle had reached peak crisis. If the commander of Eighth Army could not stand up to this, he had no place in the command tent.

By 25 Nomber 1941 the commander the army needed was clearly not Gen. Cunningham anymore. It did get Ritchie by name, but Auchinleck in reality, and recovered from the early reverses of the battle through a mix of mistakes by Rommel, ruthless command aggression by Auchinleck and skillful defending, which destroyed most of what remained of the Axis tank force.