Background

Operation CRUSADER marked another step in the development of the Close Air Support doctrine and mechanics in the Royal Air Force. (1) The system is very well described in AIR2/5420, a report by Wing Commander Geddes RAAF, who represented the Army Co-Operation Command, and served as RAF Liason Officer at the Corps HQ of 13 Corps, and then at 8 Army HQ. The report was a bit of an embarrassment to higher commands, who tried very hard to suppress it, because the points made in it on standards of training and discipline were not too comfortable.

The RAF army co-operation system established for CRUSADER, while it was to undergo heavy modification and refinement, was the foundation upon which the very successful air support system that was in action in Normandy was to be built. The development of the system was based on the very close working relationship between the commanders of the ground and air forces at the highest levels of command. What many people do not realize is that this system was at the time far superior to that of the German forces in North Africa in terms of integrating air force liason sections with low-level commands (down to Brigade level). This superiority was partially driven by superior numbers of planes being available, and partially by a real desire to improve co-operation between the arms of combat. In the Panzerarmee, this level of co-operation would not happen until 1942, and during CRUSADER the German arms of service operated on a looser co-operation basis at the frontline.

As Mike Bechthold notes, the system originated with Air Commodore Collishaw, who had however been replaced with Coningham by the time of CRUSADER.

Air Commodore R Collishaw, the Air Officer Commanding No. 202 Group, surveys the ruined buildings on the airfield at El Adem, Libya, following its capture on 5 January 1941 during the advance on Tobruk. (IWM CM 399)

Like in the Wehrmacht in general, the system developed by the Western Desert Air Force rested on increased availability of wireless sets, the close integration of air force and army at the tip of the advance, and the assignment of specific squadrons to air support missions.

Structure

Key elements of the system were:

- The creation of Air Support Controls to be attached to the Corps HQs. No. 1 (Australian) being assigned to 13 Corps, and ‘T’ to 30 Corps. The other active units by the time of the battle was 2 New Zealand, but I do not know where this was assigned to.(2)

- The Air Support Controls were in charge of RAF sections (tentacles) attached to low-level (Brigade/Division) staffs of the ground force, and in radio contact with higher level RAF commands with the aim of passing on reconnaissance results. Tentacles were allotted to lower-level commands by the Controls, depending on need.

- Selection of targets only by air tactical reconnaissance, since it was felt that there was insufficient ground observation. In reality however, this seems to have been about equal between tactical reconnaissance and the ground tentacles.

- Fully centralized control of strikes – all requests were passed to A.O.C. (Air Vice Marshal Coningham) at RAF Western Desert HQ for consideration. Corps HQs would not sift targets but would only pass on information to A.O.C., and provide army co-operation squadrons with advance warning that they might be called on to attack.

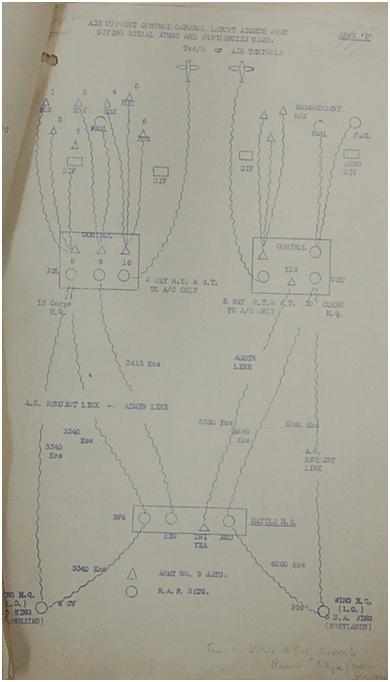

The figure below describes the system.

The RAF/Commonwealth Ground Force Liason System for CRUSADER

(Appendix to Report by Wing Cdr Geddes, TNA AIR2/5420)

Forces and weapons

Forces allocated to army co-operation were No. 270 Wing (RAF, equipped with Bristol Blenheim light bombers) to 13 Corps, and No. 3 Wing (SAAF, equipped with Martin Marylands) to 30 Corps. It must be recognized however that these units were not exclusively tasked with army co-operation, but would be required to support the primary mission (gain and maintain air superiority) if deemed necessary, by e.g. attacking airfields in the rear, or indeed to attack other targets of opportunity not directly involved in the ground battle. This seems to have been in particular the case with No. 12 Squadron SAAF, which spent some time in late November at rear area interdiction. In the case of both the South African Maryland squadrons, they also famously engaged in chasing Ju 52 transport planes for a few days in December. The war diaries of No. 12 and No. 21 Squadron SAAF are available online and make interesting reading.

Martin Maryland, ‘O’, of No. 21 Squadron SAAF flies over the target as bombs explode among poorly dispersed enemy vehicles of the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions east of Sidi Rezegh, where they had assembled with the intention of breaking through the British positions at Bir el Gubi.

(Picture from Imperial War Museum – IWM CM 1561)

In addition to these light bombers, each Corps and the 8 Army HQ had a squadron of Hurricane I photo reconnaissance planes permanently attached to it (No. 451 Squadron RAAF to 13 Corps and No. 208 Squadron RAF to 30 Corps. No. 237 (Rhodesian) Squadron was in ‘reserve’ at 8 Army HQ. These squadrons flew unarmed Hawker Hurricane I fighters, which had additional fuel tanks instead of guns in the wings. They would normally be accompanied by fighters for their protection, but the Squadron providing this, No. 33 RAF, had been withdrawn and assigned to operate in the Axis rear from a new Landing Ground behind enemy lines, just before the battle.

Photographers of an army co-operation squadron use a portable darkroom to develop aerial reconnaissance film at a landing ground in the Western Desert, while a pilot of a tactical reconnaissance Hawker Hurricane, seen in the background, waits to see the results (right).

(Picture from Imperial War Museum – IWM CM 1648)

At the time of CRUSADER, weapons for ground support were not well advanced. The main weapon used by the Western Desert Air Force for direct air support was the 250lb general purpose bomb, and machine guns and cannon were also heavily used. The 250lb bomb relied on being relatively close to its target to have much of an impact. Against a well-dispersed ground target such as a transport column, and especially against armour, it was unlikely to be a successful weapon.

Armourers preparing to load a Martin Maryland of No. 39 Squadron RAF with its full complement of eight 250-lb GP bombs, at a landing ground in the Western Desert.

Picture from Imperial War Museum – IWM CM 1100)

The Hurricanes used for ground support were only equipped with British .303 MGs and some probably with 20mm Oerlikon cannons, both of which were weapons too weak to make any impression against even lightly armoured or dug-in targets. Only one squadron of ‘Hurribombers’ was available, No. 80 Squadron RAF. The need for a proper ‘tank-busting’ fighter aircraft was recognized immediately after the operation, and led to the development of the 40mm cannon-armed Hurricane Mk. IID, which entered service in the desert in summer 1942.

Pilots of No. 80 Squadron RAF gather in front of one of their Hawker Hurricane Mark Is at a landing ground in the Western Desert, during Operation CRUSADER. In the middle of the group, wearing a white flying overall and smoking a pipe, is Squadron Leader M M Stephens, who commanded the Squadron from November until 9 December 1941 when he was shot down and wounded. During CRUSADER, 80 Squadron acted in close support of the Army, their Hurricane fighters being fitted with bomb racks to carry four 40 lb GP bombs, as seen here. Their first effective sorties as fighter-bombers were conducted against enemy vehicles south of Bir el Baheira on 20 November.

Picture from Imperial War Museum – IWM CM 1725)

By comparison, on the German side only Panzergruppe HQ had a permanent unit attached to it, 2(H)14, which consisted of a mix of figher and reconnaissance planes. On the other hand, the Germans and Italians had considerable strike forces in the form of Ju 87 dive bombers, and converted Fiat CR 42 biplane fighter-bombers which were available to support their ground forces.

Results

It is unlikely that the battle was very much affected by direct (i.e. during the battle) air support on either side. Ordnance delivered was too weak to affect the outcome, and insufficient in volume and accuracy. Reasons for this are varied:

- The fundamental reason was a lack of aircraft to achieve the different missions. With the clear recognition that air superiority was more critical than anything else, army co-operation came second, followed by army protection last.

-

The delay between ordering up and receiving a strike was too long, with 2.5 hours apparently being the normal time. Delays were driven by

- the centralized nature of the system, by the distance of strike forces from the battlefield;

- the need for dispersal of aircraft at the landing grounds which added to take-off times;

- the nature of the air fields which often made simultaneous take-offs impossible, requiring forming up in the air; and

- the need to protect bombers with fighter escorts in an air space that was not fully controlled leading to a delay in order to enable the rendez-vous; and

- finally by the lack of training of both air and ground crew, which led to delays in bombing up and relatively lower standards of training than in the UK, including the experience of the air crews in flying impromptu, rather than deliberate missions (3).

- the centralized nature of the system, by the distance of strike forces from the battlefield;

- Finding the target, in a landscape bereft of landmarks.

- When the strike then came, it had to struggle to correctly identify the target, which was difficult already because of visibility conditions, but made more so by the heavy reliance of the Axis forces on captured Commonwealth transport. Identification from the air was a major issue for both sides, and ‘friendly’ fire incidents occurred with what must have been irritating regularity.

- Finally, even if the strike found its target and identified it correctly, the weapons available were hardly suitable.

- It is of note that while provision was already made for artillery spotting from the air by the army co-operation squadrons, this method was not employed much due to the fluid nature of the battle. But when it was used it was deemed successful.

During the last exercises in November, the following time delays were given by Geddes as average examples which were not much improved upon during operations: 2hrs 32mins, 2hrs 15mins, and 2hrs 40mins.

Looking through the war diary of No. 21 Squadron SAAF (Marylands), they seem to have managed a normal rate of only one sortie per day during the height of the battle. Considering the short daylight hours, the transmission and decision time, and the duration of a sortie (even excluding briefing and bombing up), this is not surprising. But it essentially restricted a squadron to being able to deliver just 18,000lbs of bombs per day. Hardly enough to make much of an impact. When two squadron sorties were made, such as by No. 21 Squadron on 26 November, it is of interest to see that the time elapsed between the first sortie returned and the second being in the air was 2 hours. The time line therefore was:

0825 Departure Sortie 1

0950 Over target

1045 Returned to base

1255 Departure Sortie 2

1420 Over target

1535 Returned to base

Based on this one would presume that this target was ground-identified (since the aerial recce plane would presumably not operate during the night), and/or may have come in the night before. The numbers also indicate that the delay from take-off to target was 1.5 hours, to which needs to be added the delay in getting the orders and briefing sorted out.

Conclusion

In the final analysis, it is arguable that the RAF system used in CRUSADER was not responsive enough to give the Commonwealth forces too much of an advantage, especially when all the other challenges of air support in the desert are considered.

While there are some examples of air support arriving in time to make a difference, e.g. during the battle for the Tobruk salient and during the march of the Afrika Korps to the east during the ‘dash for the wire’, most of the impact is likely to have been caused by:

- Interdiction of supply by attacking truck columns on the Via Balbia

- The successful battle for strategic air superiority which prevented the Axis air forces from major interference in the ground battle

- Finally, by the provision of strategic and tactical reconnaissance by air.

Nevertheless, the system showed up many issues that would have to be addressed to move forward towards the implementation of a workable and effective ground support arm within the Royal Air Force. The planners in Cairo had done a reasonable job in making sure that their objective was appropriate to their means, which were not rich during the period, both in numbers or capability. Furthermore, the desert in winter had its own challenges, including the weather, and the lack of daylight.

Even today, air forces overclaim the impact that their support has on the battlefield, so plus ca change, ca change jamais… So it would be an interesting question to see whether it might not have been better to focus the resources purely on non-battlefield missions, such as interdiction of supplies. One thing is certain, if the light bomber squadrons had been tasked for deliberate missions, instead of sitting around at their airfields waiting for the machinery to crank into action, they could almost certainly have more than doubled their sortie rate. It is easy to see three missions a day being arranged like that.

1st thing in the morning – briefing for the day

Early AM – 1st mission to Via Balbia west of Tobruk for attack on supply columns/dumps

Late AM – 2nd mission to Axis by-pass road, positions on Tobruk perimeter, dumps

Afternoon – 3rd mission to Bardia/Halfaya positions

Such an arrangement would not have precluded throwing in impromptu missions on return from the earlier missions.

What worked:

A petrol tanker and trailer on fire on the road between Homs and Misurata, Libya, after an attack by Bristol Blenheims interdicting enemy fuel supplies in support of Operation CRUSADER.

(Picture from Imperial War Museum – IWM CM 1500)

Notes

(1) As the official history by Denis and Saunders states: “All the same, the months from July to November 1941 saw Tedder and his staff, acting partly in the light of principles already enunciated by Army Co-operation Command but still more in the light of their own experience, hammer out a system of thoroughly effective air support. It was to serve the Army well not only in the deserts of Africa but also, with later refinements and additions, among the swift rivers and frowning mountains of Italy, the green hills and woods of Normandy, and the sombre plains and broken cities of the Reich itself.”

(2) These are described in the official history as follows: “These were mobile units whose duty was to consider, sift and relay requests for air support. They were manned by the Royal Air Force, with a small Army staff attached, and located at the headquarters of each corps. From them four main channels of communication branched out–to the forward infantry brigades in the field (an Army responsibility), to aircraft in the air, to the landing grounds, and to advanced Air Headquarters, Western Desert.”

(3) The official history comments in that marvelously English way as follows on this matter: “By the end of 1941 the general standard of operational efficiency was steadily improving.”

Sources

AIR2/5420 – Report by Wing Commander Geddes on Libyan Offensive, March 1942

AIR54/51 and 63 – ORBs of No. 12 and No. 21 Squadrons SAAF

Australian War Memorial – Operational Histories WW2 – Air Vol. 3 Chapter 9 ‘Second Libyan Campaign’ (note that the diagram and description of the system in operation on page 194f does not appear to be correct, since it states that the Air Support Controls could decide about strikes)

Denis, R. and Saunders, A. Royal Air Force 1939 to 1945 Vol. II ‘Fight Avails’

Hyperlinks to other sources provided in the text.

Pingback: Ground Support in the Desert, 1941 - World War 2 Talk

Pingback: Operation Report No. 12 S.A.A.F. Squadron 29 Nov 41 « The Crusader Project

Santoro talks about this in his book vol II. The troubles that Rommel sowed in fights with Luftwaffe and with 5ªSquadra.

Plus in pages 125 and following refers Churchill intervention was needed.

LikeLike

Happy New Year Andreas.

Good post. Bidwell covers a lot of this ground in his book ‘Firepower’. There’s also been a relative flood of books and articles over the last decade or two about the development of the RAFs air-ground technique.These include:

* Gooderson’s ‘Airpower at the battlefront’ (thesis and book),

* Bechthold’s ‘A Question of Success’ (journal),

* Hall ‘Learning how to fight together’ (paper at Air Force Research Institute),

* Jacobs ‘Air Support for the British Army, 1939-1943’ (journal),

* Johnston ‘The Question of British Influence on US Tactical Air Power in World War II’ (journal),

* Steadman ‘A Comparative Look at Air-Ground Support Doctrine and Practice in World War II’ (journal),

* Parkin ‘Creation of the Australian Manual of Direct Air Support, June 1942’ (journal)

I seem to recall that there was one – admittedly exceptional – instance during CRUSADER in which the time from request till the RAF got bombs-on-the-target was just 30 minutes.

Jon

LikeLike

Pingback: Notes from the Receiving End « The Crusader Project

Dear Sir,

A very interesting article. I have a question for you, if possible to answer. Where was situated the airfield used by the British for Close Air Support along Crusader Operation? Was used any of the al least five airfield inside Tobruk area?

Thank you very much.

Carlos C.

LikeLike

Dear Carlos

As far as I can see none of the airfields were used as a base during this period. Only after the middle of December did e.g. El Adem come into action.

In the first period the airfields were close to the border, towards the south of Capuzzo.

I hope this helps.

All the best

Andreas

LikeLike

This article mentioned that the war diaries of 12 squadron are available online, where can I find them?

LikeLike

… I will have to look again

LikeLike

Pingback: Book Review: “Flying to Victory” by Mike Bechthold – The Crusader Project