Background

Operation CRUSADER is generally supposed to have started on 17 November 1941. This is however not fully correct. While the ground operations commenced on that date air as well as naval operations had begun considerably earlier. An increasing bombing offensive began in October 1941, targeting major Axis logistics centres as well as supply routes and known troop concentration areas. At sea, Force K had been placed into Malta by about the 20th of October with a clear mission to interdict Axis supplies across theMediterranean. Given that operation CRUSADER was a multi spectrum offensive, it is therefore arguable that it had in effect begun by about the middle of October 1941.

September 1943, Italy. Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder on the Italian coast. Later that month he returned to Britain to take up his appointment as Deputy Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces then being assembled for the cross-channel invasion. IWM TR1487

Air Marshall Tedder

Air Marshall Tedder was the overall commander of Empire air forces in the Middle East. He was subordinate to General Auchinleck as commander in chief but also had a direct communications line too London and the Chief of the Air Staff. He remained in constant communications with Air Chief Marshall Portal throughout the operation.

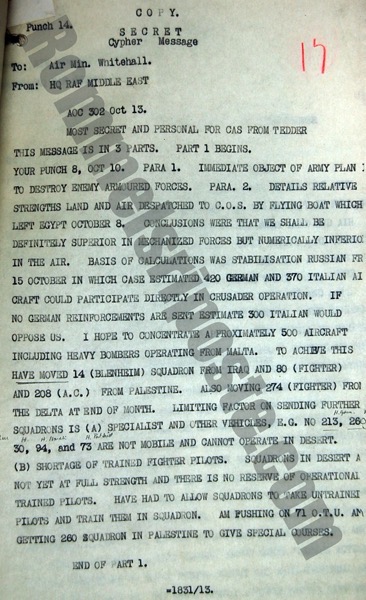

The document below is an appreciation of the situation by Air Marshall Tedder, issued in preparation for the offensive. It outlines his concerns about the likely strength disparity between the Axis air forces and his own force and the measures taken to address them. The full length of the appreciation is three pages, only the first of which is produced below. The other two are more operationally focused.

As Mike Bechtold (see this link), notes, it is also possible that the appreciation was meant to serve as an explanatory note in advance for why the newly ordered air support system had failed in the forthcoming operation.

Telegram, Tedder to C.A.S. Air Chief Marshal Portal, 13-Oct-1941. TNA, Kew. Rommelsriposte.com Collection

The Axis Position

A key concern was the expectation that the Empire air force would be numerically inferior, an expectation that was not borne out in the end. Neither the Luftwaffe nor the Regia Aeronautica reached the numbers of planes he feared. For example, on 27 December, the Luftwaffe had only 115 planes available in North Africa, with many having been withdrawn. Serviceable numbers were much lower. The Regia Aeronautica reported 134 planes the same day, effective. The combined effective numbers did not reach above 200, if that much. More importantly, while there was reinforcement of the Axis air force (e.g. through modern Mc.202 & Bf109F4 fighters), by the time it arrived logistics trumped all and the Axis air forces were running out of petrol to get their planes in the air. This was a hard fought campaign on, over and under the waters of the Mediterranean. It cost the Royal Navy a battleship, an aircraft carrier, two cruisers, and a number of smaller vessels and submarines. The Royal Air Force lost a large number of Blenheims and their crew. But the effort paid off, and by the middle of December German planes could only manage one sortie a day, and numbers were withdrawn.

Priorities

What is interesting in Tedder’s appreciation is that other than raw numbers of planes, there were real constraints on the softer aspects of air power, crews and mobility. A lack of trained pilots is surprising, as is a lack of vehicles to make squadrons mobile, considering the Middle East should have been the primary theatre of war for the United Kingdom. The lack of trained fighter pilots which on operations would translate into pilots with low hours and experience is perhaps one reason for the oft observed challenges that Empire fighter pilots faced when encountering Axis opponents. The inability to bring more squadrons forward due to a lack of vehicles meant that the burden on those who were forward was all the harder.

This to me reinforces the idea that the Royal Air Force treated the only theatre where the Empire forces were in ground combat with the Axis with some contempt or more politely neglect, not allocating modern fighters, rather relying on US built P40s being delivered via the Takoradi rout and hoping for the best, and providing insufficient pilots. Nevertheless, at the same time as Spitfires and trained pilots were wasted on pointless fighter sweeps and CIRCUS operations over France, the Middle East had to make do with 2nd-line equipment such as Hurricane Is who had to soldier on in frontline service. The CIRCUS offensive was not abandoned until November 1941, when it had cost far too many planes and pilots, while not achieving its operational or strategic objectives.

Air Chief Marshal Sir William Sholto Douglas, Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, RAF Middle East Command (left) with Air Officer Commanding Malta, Air Marshal Sir Keith Park in the garden at HQ, Malta. IWM via Wikipedia.

Air Chief Marshal Sir William Sholto Douglas, Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, RAF Middle East Command (left) with Air Officer Commanding Malta, Air Marshal Sir Keith Park in the garden at HQ, Malta. IWM via Wikipedia.

The Campaign

The Desert Air Force was given two massive breaks even before the first shot was fired on the ground. First the Germans continued the offensive on Moscow, meaning that transferring planes to the Mediterranean theatre would have to wait. This was something Tedder probably wasn’t aware of when he drafted this message, and secondly the torrential rainstorms lashing the desert on 17 November which grounded all their planes (see this link). This gave the Empire air forces an advantage that they would not let go.

Furthermore, the strategic limitations of the Axis became plainly visible during the campaign. Only one side succeeded in fighting a combined air/sea/ground battle. There is much focus on Rommel’s performance on the ground, but in doing so it is easy to fail to grasp the bigger picture, that despite all the squabbles in Cairo and between Cairo and London, the Middle East integrated command structure was working for the Empire. This is in my view why, after being beaten on the ground repeatedly in the worst possible way for the best part of two months, and generally not doing much better in the air the Empire forces prevailed. Because an integrated force can do badly even in multiple spectrums of war against an enemy who doesn’t fight an integrated battle.

The victories on the ground were deceiving. On 2 Dec 41 Rommel thought he had won a great victory (see this link), but only two days later, after he had met with Colonello Montezemolo of Comando Supremo, who took him through the dire logistics situation following the failure of two major convoys in November, when the Beta or Duisburg convoy was destroyed by Force K and the Gamma convoy two weeks later had to return to Italy when two accompanying cruisers were torpedoed and damaged, he had to concede that there was no possibility to prevail and that the siege of Tobruk had to be lifted (see this link).

Indian Soldiers examine an abandoned Italian M13/40 tank of Ariete Division in Benghazi, end of December 1941. IWM

The Axis forces then retreated orderly, first to the Gazala line and then onwards to Agedabia and Agheila, ending up on 7 January 1942 where they started in April 1941, licking their wounds, but preparing for their turn, which would come soon enough. The border posts of Bardia and Halfaya fell in due course, having been abandoned hundreds of miles in the rear of the Empire forces.

Further Reading

IWM on Circus Operations over France

“There is much focus on Rommel’s performance on the ground, but in doing so it is easy to fail to grasp the bigger picture, that despite all the squabbles in Cairo and between Cairo and London, the Middle East integrated command structure was working for the Empire. This is in my view why, after being beaten on the ground repeatedly in the worst possible way for the best part of two months, and generally not doing much better in the air the Empire forces prevailed. Because an integrated force can do badly even in multiple spectrums of war against an enemy who doesn’t fight an integrated battle.”

I think this is the key element in comprehending Axis performance in many theaters, not just in North Africa. At the tactical level, the Germans were very impressive, racking up huge kill ratios in the air, against enemy tanks, even the slow moving Allied infantrymen. Yet, once you get past their undeniable tactical successes, the Germans simply do not have the ability to maintain the operational tempo required. Their sustainment capabilities are insufficient to keep their forces supplied with the necessary ammunition, gasoline and replacements to exploit any victory. The Allies attack the Axis on all domains, and are able to degrade the Axis logistics vulnerability at sea (just enough) to cause Rommel to culminate and retreat, regardless of how many British armored brigades he has savaged (all of them I think). The Germans are typically lauded for their planning abilities, but in this case the Allies do better by incorporating their maritime assets into their campaign plan, and synchronizing them with their land and air operations better than the Axis can. It’s an ugly win, but a win nonetheless. And winning matters.

LikeLike