Porträt Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel mit Ritterkreuz und Orden Pour le Mérite (BAMA via Wikimedia)

Introduction

One of the enduring images of the desert war is that of the rapidly advancing Afrikakorps sweeping all before it. This is certainly what happened in April 1941 during the re-conquest of the Cyrenaica and Marmarica provinces of Libya. It led to considerable gains of terrain for the Axis, and losses in men and equipment for the Empire forces. The offensive culminated in the siege of Tobruk. This advance was against clear orders given to Rommel, namely to await the arrival of 15. Panzerdivision in May 1941 before commencing operations. This was of course of major propaganda value, and it has shaped the image we have of Rommel today, with a victorious German force (the Italians are normally overlooked) advancing rapidly, encircling and defeating all before them.

Raids however (the Wehrmacht used the same term) were allowed, as long as they did not end with the occupation of terrain. These were presumably considered useful in that they would keep the Empire forces off balance, and would deny them peace and quiet during which to prepare for their planned advance on Tripoli. Rommel commenced his raid on Agedabia, and when testing the Empire defenses found them weak. He then took the opportunity to unleash his forces for a deep penetration into Cyrenaica, with the aim to completely defeat the enemy in the western desert.

At the end of April, Rommel found himself in a tricky situation, far away from his supply sources, with dispersed and weakened forces, and exposed to Empire counter attacks on the line of the frontier between Libya and Egypt. What rescued his force at this point was the thundering defeat that had been suffered by the Empire forces in Greece, which prevented Middle East Command from taking advantage of this weakness. By the time sufficient forces could be scrounged together in Egypt, the moment had passed, with the arrival of the first elements of 15. Panzerdivision in the area of operations. The first co-ordinated Empire counter-offensive, BREVITY, came about two weeks too late, and the desert war settled into a pattern of periodic offensives and counteroffensives for half a year.

The outcome of this initial offensive was that the Axis forces in North Africa were strung out, at the end of a precarious supply line, and highly exposed. This had been foreseen in Berlin, but not appreciated by Rommel, who did not have much interest in the question of logistics. The modern assessment of this initial offensive is that it ultimately doomed the Axis effort in North Africa. This article sets this out in more detail, drawing on period documents and participant views.

Nordafrika.- Panzer III in Fahrt durch die Wüste (Panzer III on the march in the desert); PK “Afrika” April 1941 (BAMA via Wikipedia)

Nordafrika.- Panzer III in Fahrt durch die Wüste (Panzer III on the march in the desert); PK “Afrika” April 1941 (BAMA via Wikipedia)

The Situation in Berlin and Planning for North Africa – March/April 1941[1]

On 1 March, Generaloberst Halder, Chief of the Staff of the Army High Command, the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH) noted that Rommel’s operational intentions needed a sound basis, and should be reviewed based on what was practically possible. Halder that day held a conference with Oberquartiermeister I (Senior General Staff Deputy Logistics) Paulus[2], who also was the First Deputy Chief of the General Staff and the Leiter Operationsabteilung (Chief of the Operations Department) General Heusinger[3], discussing the situation in Libya, and Rommel’s preparations for the forthcoming attack. These men were the top trio of the German army’s operational planning. Later that day Major Ehlert, the designated Ia (chief operations officer) of the Afrikakorps reported in, and was briefed on the ideas of the army leadership regarding offensive operations in North Africa.

On 3 March, a discussion was held between Halder with Field Marshal von Brauchitsch[4] regarding the offensive possibilities in the short and longer term, when it was expected that troops could be released from Barbarossa.

On 7 March Kapitän (or army Captain) von Both, who had been on an inspection tour to Libya, reported back to the OKH. He noted that supply services should be centralized, and that the supply route to Libya, via Rome and Naples, had room for improvement.

On 10 March, another conference with von Brauchitsch was held in which General Heusinger noted that Rommel had been instructed not to advance his front too far ahead before the arrival of 5. lei. Div., and sufficient Italian forces.

On 12 March, the following offensive options were set out for North Africa by the Generalquartiermeister (Quartermaster General), Gen. Wagner[5]:

a) Mounting a major offensive from Agedabia with the main thrust on Tobruk.

b) Starting several minor offensives in sectors along the coast.

Wagner assessed that the first option would require four supply column battalions in addition to the four already in Libya, while the second option was possible with the four that were already sent, but would lead to a loss of time and lower striking power. A memorandum to OKW was requested. This needs to be seen in the context that the Afrikakorps already had substantially better supply capacity than the Army Groups tasked for Operation Barbarossa, far in excess of the divisional slices allocated to these.[6]

German Map of North African Theatre, showing situation on 30 April 1942. Rommelsriposte.com Collection.

On 14 March Halder notes that there were difficulties with the Italian commander in North Africa, General Graziani, who was soon to be relieved by General Gariboldi. Also, a report was made by Oberquartiermeister IV[7], which estimated that fifteen British divisions, including two armoured, were in North Africa, of which four to eight, including the armoured divisions, were in Libya. This was a considerable over estimate of the British forces then available, and also did not seem to consider the demand of the Greek expedition.

On 17 March a general staff conference was held with Hitler, where he agreed to a forward shift of the defensive line in North Africa, and that preparations should be made to allow an offensive once a favorable force balance had been attained. He did however decline the sending of further troops, as well as the conduct of a landing operation in Tunisia, which had been the wish of the Italians.

On 20 March Rommel presented his plans to the OKH in person, on his overall impression of the situation, the operational situation, and what was possible in terms of operations with the forces available. The two leaders of the supply department of the German Army, the Oberquartiermeister I and the Generalquartiermeister, then conferred with Rommel, and he was tasked to present an estimate of what could be achieved with the available forces prior to the onset of the hot season.

According to Halder, the assessment by Rommel was that the British were passive, and focused on defense, treating the area around Agedabia as no-man’s land. It was expected that their defense would focus on the Jebel Akhdar area to the north of Cyrenaica. This was considered to eliminate the possibility of an attack on Tobruk via Msus, on the direct line through the desert, until the British forces in the Jebel were beaten. This was a task the Afrikakorps was not considered to be capable of at this stage, and consideration was instead given to occupying the area around Agedabia, and to prepare for a drive on Tobruk in fall 1941.

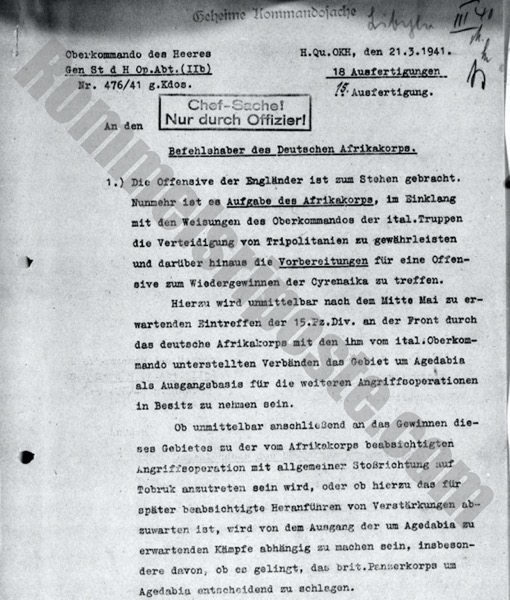

In the afternoon of the same day Paulus reported back to Halder on his meeting with Rommel, in line with the situation as set out above. This discussion led to the issuance of an order from von Brauchitsch to Rommel, as below. It sets out the tasks of the Afrikakorps. These are to work with the Italians to ensure the defense of Tripolitania, and to prepare for offensive operations to recapture Cyrenaica. The first step for this was to take the area around Agedabia, after the arrival of the whole of 15. Panzerdivision in the middle of May 1941. A further advance on Tobruk was then dependent on whether the battle of Agedabia would lead to a decisive defeat of the British armoured forces.

ObdH Order to Rommel, 21 March 1941. NARA T-78 R324

Rommel in the Rommel Papers recalls from the meeting that he was not happy at what he saw as efforts by von Brauchitsch and Halder to keep down the numbers of troops sent to Africa, since this in his view left the future of the campaign there to chance. He also considered that the in his view momentary British weakness in North Africa should have been exploited energetically, in order to gain the initiative once and for all for ourselves.

Following this visit by Rommel, there is little consideration for North Africa in the war diary of Halder, since the rapidly escalating situation in Yugoslavia and the Greece demanded the full attention of the OKH until the end of April. Thus Libya took a backseat, other than an observation by Gen. Wagner, based on the report by one of his officers, on 1 April that Rommel showed no interest in supply, and that supply vehicles remained idle in Naples, rather than being shipped.

On 3 April then the report arrived in Berlin that Agedabia has been taken. This brought North Africa back up the agenda, and it lead to a direct order from Hitler through the Armed Forces High Command channel (the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht – OKW) that first congratulated the Afrikakorps, but then made it clear that there was no room for recklessness, no Italian reinforcements could be expected, and Luftwaffe assets were soon to be withdrawn for the campaign in the Balkans. Any further advance was only authorized if it was clear that Empire tank forces had been withdrawn. For some reason, this order was interpreted by Rommel as giving him “complete freedom of action” (see the war diary entry at this link and also The Rommel Papers).

On the same day, Rommel writes to his wife (emphasis by me):

We’ve been attacking since the 31st with dazzling success. There’ll be consternation amongst our masters in Tripoli and Rome, perhaps in Berlin too. I took the risk against all orders and instructions because the opportunity seemed favourable. No doubt it will all be pronounced good later and they’ll all say they’d have done exactly the same in my place. We’ve already reached our first objective, which we weren’t supposed tc get to until the end of May. The British are falling over each other to get away. Our casualties small.[…]

On 11 April, Halder notes Wagner’s comment that Rommel was now making “preposterous” demands that could only be satisfied as long as the preparations for Barbarossa were not affected.

On 13 April, Halder notes that Hitler was considering adding a motorised infantry regiment to North Africa, which had previously been refused by the OKH, on the following grounds:

a) Matter had been considered for a long time

b) No spare troops considering need for task Barbarossa

c) No shipping available until May when all units of 15. Panzer had reached North Africa.

d) Impracticable given lack of transport and fuel.

e) Lack of air support made embarking on large-scale operations unwise.

f) Getting closer to Egypt, British resistance would stiffen.

On the same day Paulus received a “colossal request” from Rommel via the liaison office in Rome, but again notes that Barbarossa has precedence.

On 14 April, two days after he has been heavily defeated at Tobruk in the Easter Battle, Rommel makes a formal request to advance to the Suez Canal, which Göring is willing to support. A discussion between Halder and Jodl (OKW) notes that this is only possible as a raid, since there were neither troops nor supply facilities available to hold Suez. Hitler then makes the final decision that the prime objective is to establish a frontline along the border from Sollum to Siwa Oasis inclusive, and apart from that only raids were to be conducted.

On 15 April, von Brauchitsch is looking for ways to support Rommel, by adding German submarines and sending the airborne division to North Africa. Halder disagrees, noting that submarines should be Italian, and also that once in North Africa, the airborne troops would be footboard. On the same day, a report from Rommel arrives, admitting that he is in trouble, and that he now requires support from two Italian divisions to shore up his position. Halder gleefully notes that “at last he is constrained to state that this forces are not sufficiently strong to allow him to take advantage of the “unique opportunities” afforded to him by the overall situation. That is the impression we have had for some time over here.”

The next day, 16 April, Gen. Wagner, following a discussion with Halder, makes reinforcements available to the Afrikakorps, to address the crisis situation. These consist of four infantry battalions, the Engineer Training Battalion (Pionierlehrbatallion, renamed Pionierbatallion 900 z.b.V.) equipped as an assault engineer battalion, and two coastal artillery battalions, H.K.A.A. 523 and H.K.A.A. 533, equipped with the powerful French 15cm GPF guns captured in 1940. Wagner noted that day that a crisis point had been reached, although not at Tobruk but at Sollum, and that this was expected to last for about 10 days, by when 15. Panzer should arrive. Wagner expected a high likelihood of Rommel being beaten at Sollum. The OKH leadership agreed that nothing could be done about this.

That same day a telegram from Rommel arrived reporting increasing pressure at Bardia, and a telegram went out to him telling him that he was on his own for the time being. Nevertheless, the transport of men to North Africa was accelerated, and on 27 April, a wave of 46 airplanes landed one rifle battalion and two rifle companies of 15. Panzer. These air transports, while not considered satisfactory, since the men would lack any equipment other than small arms, was to continue the next day.

On 5 May, Kapitän zur See Loyke reported from Libya with the insight that as long as Malta was held by the British, no offensive east was possible for Rommel.

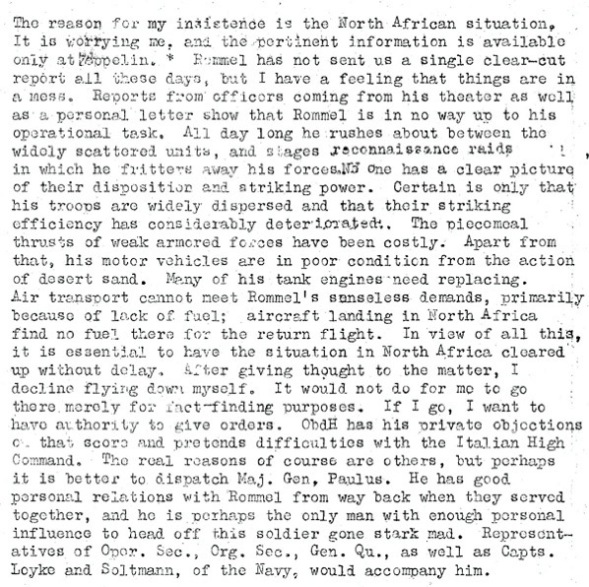

Halder War Diary Entry, 23 April 1941, famous for calling Rommel ‘this soldier gone stark mad’, and rather belying Rommel’s expectation in his letter of 3 April that all would be pronounced good.

A Counterfactual Approach

Modern historiography has not been kind about Rommel’s rash advance in defiance of orders from Berlin, and the general view today is that Rommel was out of his depth and never really got to grips with the logistical challenges his theatre forced him to confront. This is discussed in detail in the official German History, Das deutsche Reich und der zweite Weltkrieg Vol. IV. which considers this advance the original sin that ultimately made victory in North Africa less likely, since it put the Axis forces into a logistically impossible situation from which they never recovered. The critical failure was that the advance failed to achieve a decisive outcome when the assaults on Tobruk in April and May failed. It is hard to disagree with this view, once one reads the Panzergruppe war diary appendices, which are a long story of supply concerns through all of 1941.

My view is that modern historiography is correct, and that the move towards the east and the conquest of Cyrenaica and Marmarica did fatally damage the ability of the Axis to sustain its campaign in North Africa. The terrain gained was worthless without Tobruk and while the losses inflicted were heavy, they were far from fatal, and both tanks and men could be replaced on the Empire side, while the drain on the Axis supply chain was permanent.

The Counterfactual Consideration

There are a few instances in the campaign in North Africa that warrant an analysis of the counterfactual, and this is one of them. What could have happened, had the advance not taken place and Rommel had stuck to the plan and his orders of 21 March? This article will provide some thoughts on the matter, based on the following assumptions:

1) The campaigns in Yugoslavia, Greece, Syria, Iraq and Abyssinia proceed unchanged.

2) There is no change to the speed of the force build-up.

3) There is no change to the force allocations on both sides.

4) The strength of the tank force on both sides is the decisive factor in the timing and outcome of any major operation.

5) Light tanks such as the Italian L3 series, the German Panzer I, and the British Vickers Mk. VI are irrelevant to combat operations.

6) Only raids are undertaken by both sides, and neither is trying to advance in strength with the intent to hold territory; any tank losses from these raids are temporary or replaced.

6) The exact numbers of the tanks available on each side don’t matter as much as long as the ball park estimate is correct. In particular for the Empire side, getting to the right numbers is very difficult, as they did not know themselves how many tanks they had available for much of the first half of 1941.

7) Both sides have logistical challenges that prevent them from concentrating fully on North Africa until the end of June 1941, in the form of other active campaigns in the Middle East, the Balkans and Greece, and East Africa. These effects cancel each other out.

Taking the above, the counterfactual will therefore focus on the tank balance, and consider when an ideal moment for battle would have come for the Axis. It is understood that this is simplistic, but it is also considered helpful to focus on the decisive element.

The North African Tank Balance to Autumn 1941

First, without the Axis advance taking place, the forces facing each other in Cyrenaica are reasonably well balanced at the end of March and early April. Including some replacements for ten tanks lost in the fire on the SS Leverkusen, by mid-April the Axis can field 75 Panzer III, 20 Panzer IV, 45 Panzer II, and 32 Panzerjaeger I, and two battalions of Italian M13/41 medium tanks, with about 100 M13/40 tanks between them. This is a total of 272 combat capable vehicles, facing 112 British cruisers[8], 60 captured Italian M tanks, and 40 I tanks, for a total of 212 tanks, of varying reliability. It is clear that this force balance does not allow the Empire forces to consider a successful offensive, and that they need to await a substantial force build-up. As the historical record shows, the balance did allow the Axis a successful, but not a decisive campaign.

TOBRUK – AN ITALIAN CARRO ARMATO M13/40 MEDIUM TANK FROM BARDIA IS TAKEN OVER BY THE AIF AND SUITABLY MARKED WITH A KANGAROO SYMBOL. TROOPER H. R. ARCHER IS THE ARTIST. (NEGATIVE BY F. HURLEY). (AWM 005047)

By early May, the Axis will receive the full force of Panzerregiment 8 as well as the other divisional units of 15. Panzerdivision in the operational zone, with the last of the tanks reaching Tripoli in the first days of May. The Axis tank force now numbers 91 Panzer II, 153 Panzer III, and 40 Panzer IV, as well as 32 Panzerjaeger I and the 100 Italian Mediums, for a total of 416 main combat vehicles.

At the same time, the Empire forces also receive reinforcements by tanks being returned from workshops, and the Tiger convoy arriving in mid-May shortly after, which enabled operation BATTLEAXE to proceed. On 7 May, prior to the arrival of the Tiger convoy, the Empire tank force, assuming the April battles did not take place, numbers 115 cruisers, 59 I-tanks, and 60 captured Italian M tanks, for a total of 234 vehicles, meaning that the Axis now has a substantial, almost 2:1 superiority in tanks fielded in North Africa. Furthermore, the Empire tank force relies still on tanks with high mileage, and a large number of captured tanks of dubious combat value.

By the end of June the picture does change, turning against the Axis. While the Italian tank force is reinforced by another battalion, bringing the total to 138 M13/40 tanks, no more German tanks are received and the Axis total rises only slightly to 454. The main additions to the Axis are now infantry formations and heavy artillery, sent in response to the failure at Tobruk. On the Empire side, further returns from workshops as well as convoy arrivals, especially the Tiger convoy, add large numbers of cruiser tanks, bringing the total to 303 available[9], and the number of I-tanks rises to 201, to bring the total to 563 tanks if we continue to include the 60 captured Italian tanks. Still in this case, over half of the Empire margin of superiority of 109 tanks is accounted for by the captured Italian tanks, and as noted it is unlikely these would have had much value in battle, given the situation with spares and ammunition. Again, in my view this makes any major Empire offensive before the end of June unlikely, and a successful one practically impossible. This is before considering the pressures of having to deal with the desaster in Greece, the campaigns in Syria and Iraq, and the need to eliminate the remaining Italian resistance in East Africa.

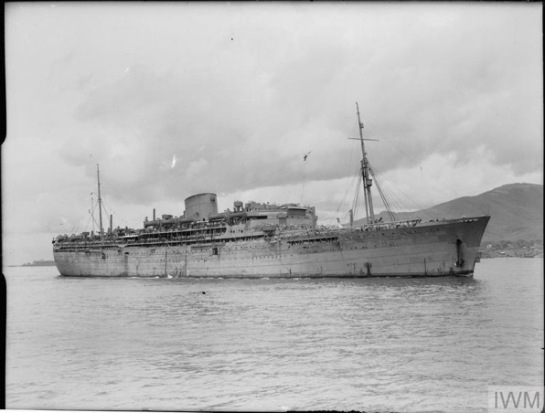

The tank balance only shifts decisively later in the summer, with the arrival of the WS9a and b convoys, and most importantly the arrival of the first M3 Stuart tanks directly from the US (detailed at this link). By September, there are 100 operational M3s in theatre, and 298 British cruisers[10], together with 298 I-tanks[11], and most importantly crews and support units had time to familiarise themselves with the new vehicle. Assuming the captured Italian tanks are now retired, the Empire tank force now numbers almost 700 vehicles, giving the Middle East Command a substantial tank margin, with which to plan and execute a substantial attack would be possible, for the first time. This would become Operation CRUSADER in the original time line.

The SS ATHLONE CASTLE transporting troops. Convoy WS19 (IWM A10610)[12]

Other considerations

Both sides benefit and suffer from the Axis not advancing to the Egyptian border. The Empire forces continue to hold Benghazi and the airfields of northern Cyrenaica, forcing Italian convoys to take the westerly route via Tunisia, where they can more easily be intercepted. They do not need to supply a besieged Tobruk, and they do not suffer the substantial distraction of an Axis force on the border during the rout in Greece and Crete. It is however unlikely that the RAF could have done much to protect the forward area and the port of Benghazi during this period, given its commitment to and losses in Greece.

On the downside therefore, Benghazi is exposed to air attack, making it an unsatisfactory port for building up an army level offensive. It needs to be kept in mind that the supply of Tobruk worked because it was for an overstrength division that was not expected to be mobile. So while the pressure on naval assets is reduced, the Empire coastal convoys are now taking a more exposed and longer route to Benghazi, and need to deliver substantially more supplies.

Given the above, it is likely that overland supply would have been key to building up for an offensive and keeping the force in western Cyrenaica supplied. The overland route from Tobruk, which would have been the safest harbour, to Mechili and west of it is hundreds of miles. Apart from the lack of tanks, the need for trucks to cover this adds substantially to the supply difficulties for a further advance. Even to support a Brigade-size forces that far west of the railhead was estimated to have taken 2,000 trucks shuttling back and forth (see this earlier entry on the planning for the BENCOL advance during CRUSADER, at this link). I consider it likely that the Egyptian railway would have been extended to Tobruk in this scenario, at least easing the supply concerns by reducing the dependence on shipping. Overall this adds to the pressure on the RAF, which is at the same time heavily committed in Greece and which poses a significant challenge to building up and maintaining a large force forward of Tobruk.

On the Axis side, conversely, the supply situation is substantially eased. The distances over which supplies are carried are much shorter, coastal convoying is possible to Sirt, and a very good main road is available. It is thus likely that the building up of supplies can be accelerated considerably.

In terms of operational opportunities, the relatively open terrain south of Agedabia allows deep raids into the Empire rear that are hard to defend against. Vehicles and men can be trained thus, while not using them up too much. The Sommernachtstraum raid of 14/15 September is an example of what would have been possible. An outflanking move into the desert, a quick hit on the Empire rear, chaos, confusion, and then retreat behind the Marada – Agheila line.

In terms of defense, the position from Marada north is relatively strong, and harder to flank due to the presence of salt marshes. An attack in the centre is possible, but would channel the attacking force considerably and expose it to hits from the north and south, similar to what happened to 22 Armoured Brigade at the end of December 1941 at Wadi el Faregh (see this link). A defense in depth, with infantry in the line, and tank forces to the rear to back them up, would have the potential to savage any attacker.

Nordafrika.- Panzer III bei Fahrt durch die Wüste, im Hintergrund brennender Lastkraftwagen (LKW); (Panzer III on march through desert, in the back burning truck) PK “Afrika” April 1941 (BAMA via Wikipedia)

Conclusion

The Empire forces were in no position to attack at Agheila or Marada prior to the end of June, simply based on tank numbers, before even getting into considerations of supply, where the need to build up substantial supplies to support not just the initial attack but an advance on Tripoli, several hundred kilometers to the west, would have taken time. From early May to the end of June the Axis tank forces and supply position would have been far superior to that of the Empire forces, inviting an attack by the Axis. No large scale operations were considered possible in the hot season from July to September.

If Rommel had waited and stuck to his orders as issued on 21 March, he would have kept the initiative until the beginning of summer at least, and would have been able to choose where and how to attack. The Axis force build-up was considerably faster than that of the Empire forces during this period, and shortening the supply lines by hundreds of kilometers, as well as not wasting precious fuel and ammunition as well as spares on the initial advance in April and the failed attempts at Tobruk would have given the Axis ample reserves to conduct a successful offensive.

An Axis attack out of the Agheila – Marada position before the end of May, with the full force of three armored divisions and substantial logistical preparation, and a substantial superiority in tanks would have promised much greater success than the lightweight attack at the end of March, and could easily have carried the Axis forces through into Egypt. This could have been planned to co-incide with the invasion of Crete, thus forcing the Empire to look into two vastly different directions at once. The planning in Berlin for an attack in mid-May was therefore clearly the right approach, since it would have maximized tank superiority, even though this was not known to the OKH planners.

Moving from a raid towards Agedabia to the full blown conquest of Cyrenaica and Marmarica in early April was was therefore a missed opportunity, lost due to the impatience and insubordination of Rommel.

Nordafrika.- Kolonne von Panzer III passieren großes Tor, (Column of Panzer III pass large gate (Arco dei Fileni)) März-Mai 1941; PK Prop.Zg. Afrika (BAMA via Wikimedia)

Featured Image: Nordafrika.- Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel im leichten Schützenpanzer Sd.Kfz. 250/3 “Greif” (Field Marshal Rommel in the light armoured personnel carrier ‘Griffon’); PK “Afrika” (BAMA via Wikimedia).

Footnotes

[1] This is based on Halder’s war diary.

[2] General Paulus, later commander of 6th Army at Stalingrad.

[3] Heusinger survived the war, and became one of the fathers of the Bundeswehr.

[4] Field Marshal von Brauchitsch was the commander of the German Army (Oberbefehlshaber des Heeres). He was sacked by Hitler in December 1941, and survived the war.

[5] General Wagner, respectively later one of the co-conspirators of 20 July 1944. He committed suicide rather than letting himself be arrested.

[7] Also of interest is an overview of transport capacity allocated to army groups and theatres on 26 April. It notes that North Africa had 2,190 tons of transport capacity, compared to e.g. 25,020 tons for Army Group Centre. In North Africa, this had to sustain 2.5 German divisions, once 15. Panzer arrived. In Army Group centre, it had to sustain 42.5 German divisions.So for about 17 times as many divisions, Army Group Centre had only 11.4 times the transport capacity, or 50% more. This likely understates the advantage given to North Africa, which had a smaller division (5. lei.), and a smaller slice of army troops.

[7] The Deputy Chief of Intelligence, General Gerhard Matzky. Under him were two departments, Foreign Armies East, and Foreign Armies West.

[8] This is assuming the 72 tanks lost by 2 Armoured Brigade during Rommel’s advance, together with the 60 captured Italian tanks which were also lost, remain present.

[9] Assuming the five tanks lost during BREVITY remain on strength as well.

[10] Assuming the 30 cruisers lost in BATTLEAXE remain on strength.

[11] Assuming the 98 I-tanks lost in BATTLEAXE remain on strength.

[12] SS Athlone Castle was a regular on the WS route and participated also in WS9b.

Sources

- Bechthold, M. Flying to Victory

- Halder, War Diary

- Munro, A. The Winston Specials.

- Parri, M. Storia dei Carristi

- Rommel, E. The Rommel Papers

- Rommel’s Riposte: NARA Loading lists for German convoys to North Africa. See this post.

- Rommel’s Riposte: Equipping a New Army

- Schreiber & Stegmann Das deutsche Reich und der zweite Weltkrieg Bd. 3

- UK TNA CAB120/253 for Empire tank numbers.

- US National Archives, Captured Documents Section, T-78 R-324, Sonnenblume OKH files.

Into Crusader Operations, Rommel lost opportunity where didn’t find to Empire supply deposits. He passed near and the Crusader Operation was very near the canceled. He was in the possession of land and he will be able to receive the reinforce for take Tobruk….

LikeLike

Regarding the Tiger convoy: It was sent through the Mediterrranean because of Rommel’s advance in April, with some tanks in deck stowage. If Rommel had not advanced, the tanks would have been in the holds and the longer circum-Africa route would have been used.

This would result in their arrival in June, and there would have been an additional 57 tanks (these were lost in the Med transit, along with 10 Hurricanes).

Side note: While the British had undoubtably taken some precautions to protect the tanks in deck stowage (tarps, etc), it was not sufficient. The resulting damage slowed the fielding of these tanks and caused the British to set standards for deck transport. This is often cited as a ‘failing’ of the British compared to the American practice. The British citing of the American practice is not, however, necessarily good. If the Americans had applied ‘deck stowage’ standards to all their tanks regardless of whether or not they were stowed in holds, it meant that there was wasted labour applying the standard and then having to undo it at the recieving port.

LikeLike

Thanks Ken, quite right.

LikeLike

Pingback: A Counterfactual Consideration of Rommel’s 1st Offensive – The Crusader Project